XII

assion, for all the talk of science and order, still fuels the artist.

Creative energy is formed of desire and a possessed drive to realize, to

manifest a thing. It is as selfless as a mother, as possessive as a lover.

Passion does not determine the content nor direct the

composition but it invigorates the artist.

Passion invokes the painter with courage to take

risks. It fills him with energy to work harder than he'd ever imagined. It

takes more work than a painting is worth at the outset but that effort soon

rewards the crafter with a manifestation of greatness that justifies even

greater application. Thankfully, the creative spirit thrives on success and as

beauty and art begin to be realized, there is energy to finish it as required.

Passion for beauty and for genius, for Beatrice who

personified these ambitions for me, drove me to endeavor to create a portrait

of this woman.

Down in my parent's basement, I was couch inclined one

summer afternoon and abusing the television remote control when there upon the

screen was the image of Beatrice. She was performing with piano accompaniment

in a small, dark local studio. There might have been a handful of viewers tuned

in. They would have been family, friends, friends of friends, and me. T'was a

fortunate happenstance and I would not click the remote to find a different

destiny. I dove instead for the VHS recorder.

Captured!

I had my cellist ensnared now and it was not in a

manner that affected her at all. No Collector, I.

In that stale environment and through videotape, the

performance lacked the magic. There was no resonance with my soul. Her passion

did not exude from the small screen. The sound and performance seemed somehow

hollow. It wouldn't do. She deserved more. The small screen did not express

her. I resolved to prove that her presence could, done properly, be

communicated through a medium. Cold I capture the passion?

The easel went up and the paint box fell open. The

turpentine and oil fumes began to fill the enclosed space of the rec room.

Paint poisons may contribute as much to the imaginations of artists as passion

ever did.

The brightly white canvas stared back at me with a

challenging, taunting air. It was not the empty board that alone dared me to be

great. It was a pale veil behind which Beatrice, ghostly white, gloweringly

appraised my worth.

Sienna, cadmium red, and ochre yellows were her

palette but also faded green might colour her intense gaze. The hues would

carve out brilliant oranges and red-browns in a suite of fiery energy. Indeed,

it would be a furnace. In the center of the frame, steady and strong, Beatrice

commands the cello in a solid, Sybilian pose.

I would depict the musician only from the shoulders

up, not allowing myself the luxury of representing movement by gesture. Amid

the dance of reds and yellows, the resonant blue of her dour décolletage

anchors the piece.

The maiden's eyes are downcast but it is not passive

reverence or contemplation. She is intently focused upon the instrument but

also looking past it. She will not meet the gaze of the viewer. No, she has no

time for spectators. This moment was not for spectators: it was for music.

The music of colours sing about Beatrice's passion yet

it is not simply the play of bright colours that would enlist an 'ooh' from the

viewer. Instead it is the transitions and expansions from the tones of her

feminine flesh, highland hair, and the dark timbre of her cello. The interplay

and exchange of naturally appearing chromatic scales range together in

splendor.

It is but the neck of the Sienna hued tool that

strives toward the upper right third of the composition from the base. The

strings are not straight but angled at the tension points where her powerful,

playful fingers push and press upon them. White against the stark dark, these

foreign lines speak of rigidity. They are slightly askew parallels against an

otherwise chaos tossed background.

The hand is blurred and fragmented, quite unfinished

in parts, unable to be frozen in place by any physical or natural order. The

splayed fingers defy static anatomy as they reach and beckon simultaneously.

Yet it is again the forehead and the holy temples of

the subject that dominates the foreground. It is her consciousness that is almost pushed forward of the canvas

by the energetic frenzy of those colours.

If the painting is bold, it portrays a fruition of the

passion that filled me throughout the creation.

Even as my still subject was stabbing bow to string,

my brush was a careening and blazing thing, gliding through the thick, pliant

surface of the oils. Rising wakes of paint would form amid the passing of the

paintbrush hairs. A landscape formed behind it of crimsons and enriched umbers

with hills and vales where once the painter's tool had passed in impassioned

decision.

All through this process, as I worked to bring the

power of Beatrice to life at my fingertips, the tape of her performance would

play and play again. The chords haunted and informed every pass, every press

and turn of the brush.

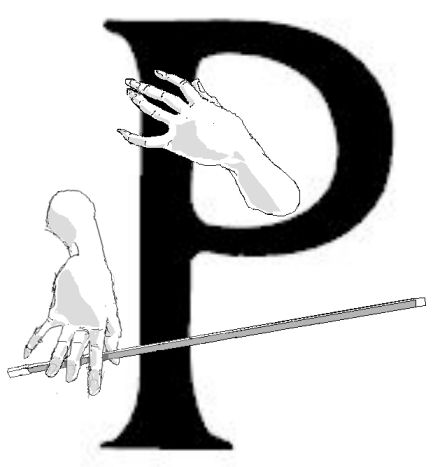

I was not passive in the process. I danced before the easel. My head and shoulders would twist and turn. My hands would sweep and sway as I strove to see clearly the flow of the composition and more to imagine and plan the exact arc and pressure of the upcoming stroke of the brush. It was a conductor that stood before his orchestral pit of paints.

The background is not simply a sea of colour. It is a tidal wash of tones that shift with the ebb and flow required of the foreground. The dreary decor of the studio wherein she was recorded was transformed in my painting to some cavernous stage of vibrant light. Vibrancy surrounds her in life. It is an aura. For all the explosion of color I employed, I in no ways exaggerated her halo.

While I toiled upon this task, my younger brother,

Duncan took my place on the sofa.

Bemused, he sat through one round of the tape but he did not remark upon

the quality, which indicated to me, at least, that he found her playing

presentable enough. In no way did I

expect that Beatrice would imbue everyone who saw her with this same

sensation. She was no messiah for

masses. This was particularly true of

her translation on videotape.

While watching my own performance, Duncan and could

but shake his head and snicker. I was

stepping back to peer and forth to paint and rolling with that dictates of

design. Painting is not a great

spectator sport.

I was obliged and this time to justify my excitement

for this woman to my family. I had to confess that I knew little of her and

that she knew so much less of me. One

thing though stood up in my defense, excused my obsession, and perhaps

rationalized it. It validated my

otherwise perverse passion and allowed them to understand a bit more of my

self.