Archduke Charles

32,000 infantry and 11,000 cavalry

March 14th, 1800

General Massena

19,00 infantry & 2,500 cavalry

Archduke Charles 32,000 infantry and 11,000 cavalry |

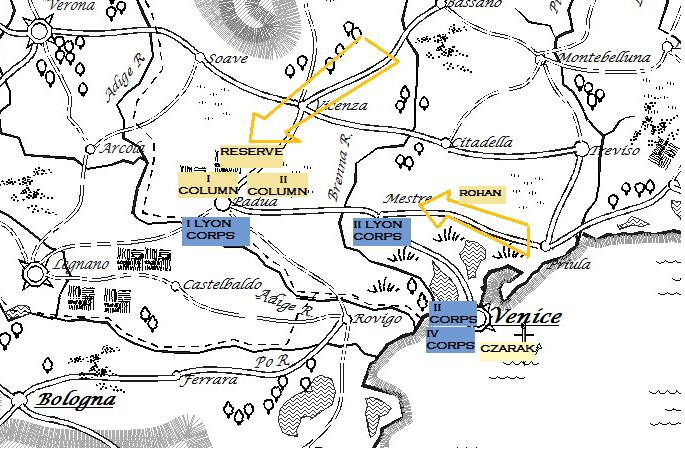

THE BATTLE OF PADUA March 14th, 1800

|

General Massena 19,00 infantry & 2,500 cavalry |

While Bonaparte continued the siege of Venice, General Massena was charged with keeping his northern flank secure. The Austrians, under Archduke Charles, had been recovering from the Battle of Soave for three weeks and had commenced a decisive march westward to try to find the French hopefully spread out north of Venice. Charles was delighted to find the French at Padua on March 14th and it was only three divisions. This should be a push over.

Rohan Division had meanwhile attacked at Mestre which succeeded perfectly in preventing the French from getting any reinforcements from the southeast.

The field around Padua seemed to offer few possibilities for the French but they chose a line behind the stream tributary of the Adige. In making that choice, the recognized that they were surrendering the road to Mestre to the Austrians.

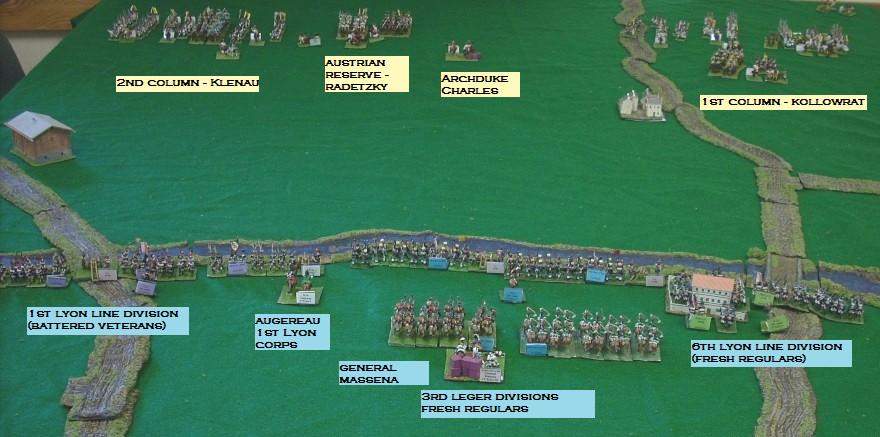

The chosen battlefield. The French are deployed in a thin line with no infantry reserves. Artillery batteries are evenly dispersed along the front.

Charles advances his strong army with little subtlety. Each column has orders to assault aggressively across the stream. More cavalry is still expected from Vicenza to join the reserve.

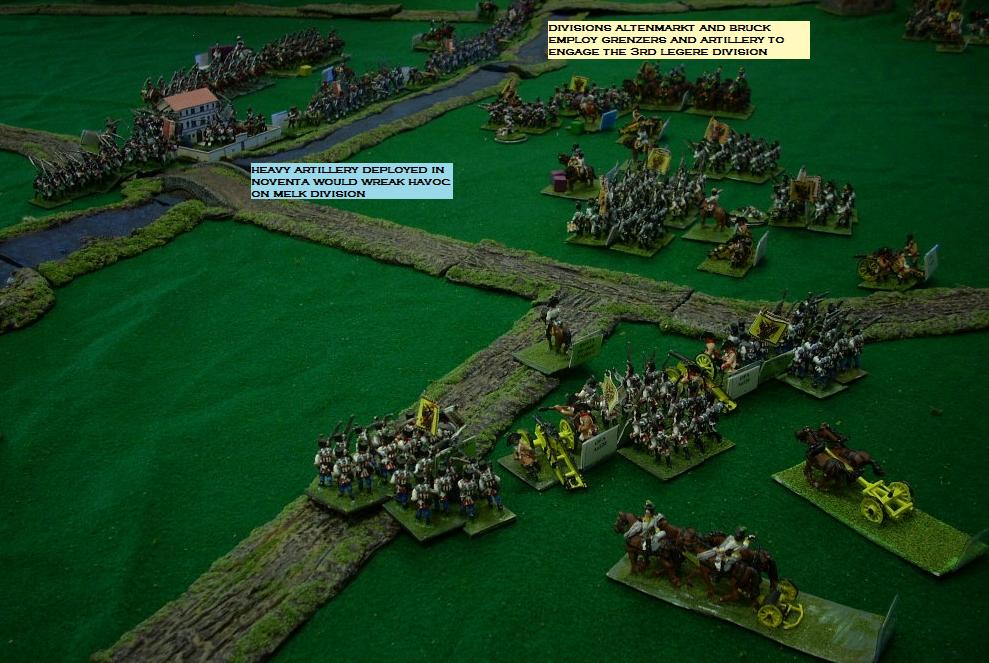

A problem that has plagued all attacking armies in this 1800 campaign has been civilian artillery drivers for the heavy artillery. The guns are obliged to be unlimbered at maximum effective range and then the civilians depart the battlefield so once positioned, the guns can do little more than prolong forward slowly.

The First column is first to the stream, sending out their advance guard and light artillery to join battle with the French. The defenders would enjoy an artillery advantage throughout the battle. On the left flank of the Austrian line, three heavy batteries are deployed and they would concentrate their fire on the extreme right of the French line.

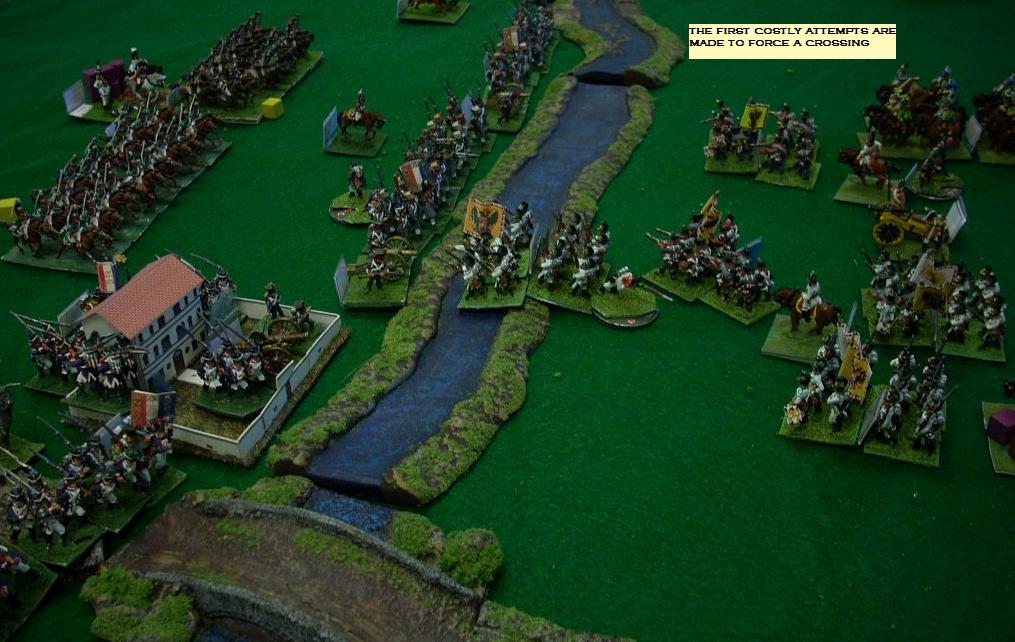

The first attempts to cross the stream are little more than screening efforts to allow the lights and artillery to work away at the infantry opposite. Even should these half-hearted attempts have succeeded, the French cavalry was poised to respond to any Austrian successes.

The Austrian Second column begins to apply pressure on the defenders, attacking evenly across the line. Sensing an opportunity, the Altenmarkt Hussars would advance recklessly into the midst of the stream.

On the left, both sides seem content to hurl cannon balls at one another. Even the musketry is telling though and losses begin to mount on both sides.

The Hussars manage to complete their charge and two brigades of Grenadiers join in. At first, all seems to go well for the Austrians but the Hussars are obliged to fall back and then the fight turns decisively in the favour of the French Grenadiers. Both Austrian grenadier brigades would be routed.

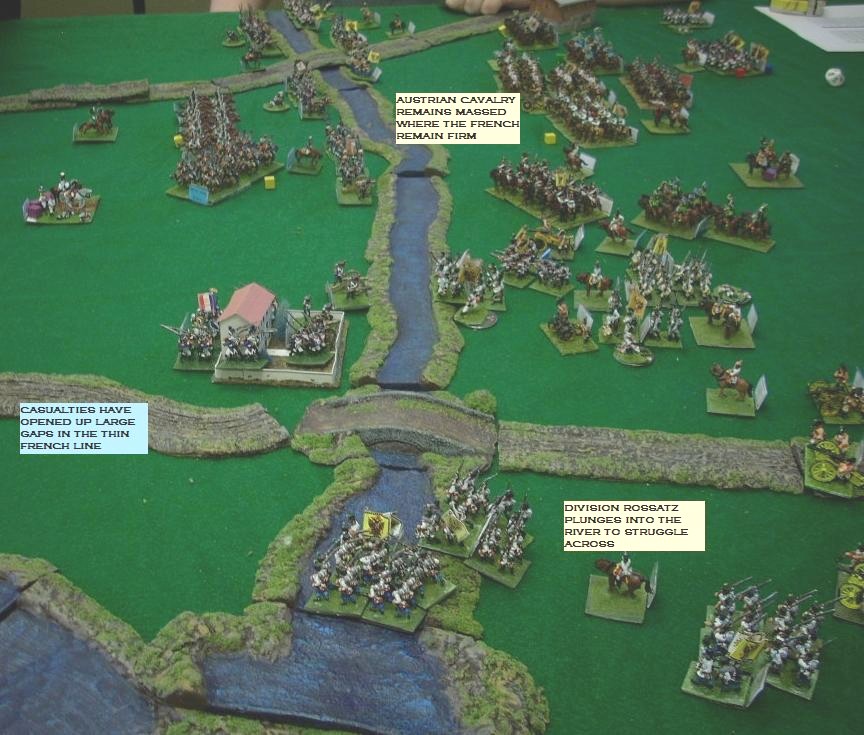

As the day wears on, three of the seven French brigades have been dispersed or routed. Gaps are appearing in the thin line. So far though, there is no opportunity for the Austrians to exploit their massive cavalry advantage. Much German horseflesh is lost due to persistent and protracted French artillery fire in the center. On the Austrian left, two openings have appeared in the French lines and the Austrian columns commence to force their way across the deep stream.

Noventa catches fire and this look very bleak for the French right. At the last minute, soldiers of the garrison manage to extinguish the blaze but the artillery is destroyed.

Evening approaches and the Austrians are surging across the stream. Massena orders a general retreat, maintaining his cavalry to conduct a rearguard action. The French would determine that Padua offers no defense either and they continue their retreat toward Legnano. Charles has achieved the victory that he was after but it has been costly and his troops are disheartened that three French divisions could have inflicted such a cost upon the Austrian Army of Itlay.